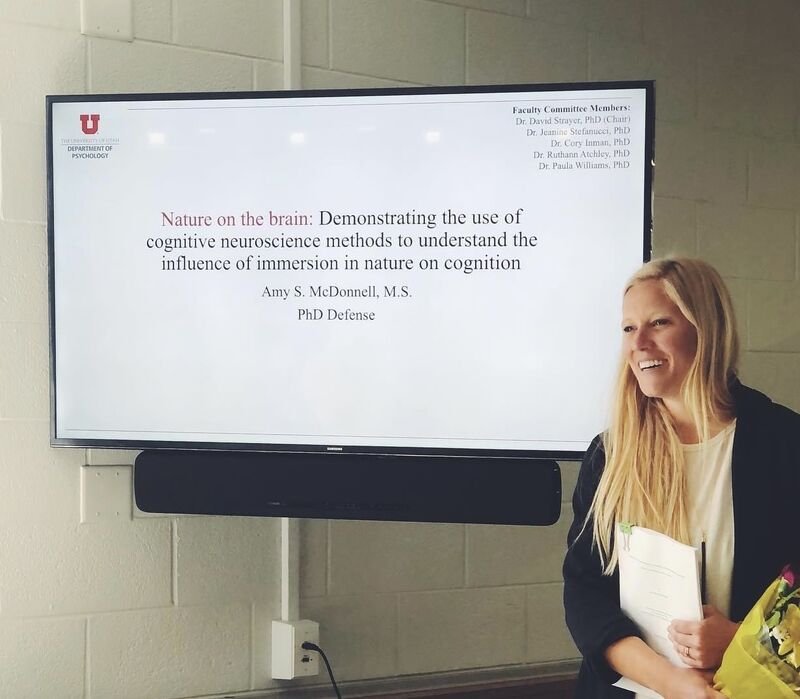

Meet the Utah Researcher Looking at How Nature Exposure Impacts the Brain

Amy McDonnell is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in Cognition and Neural Science at the University of Utah. Her research involves real-world experiments outside of a lab to measure the benefits of nature on certain facets of mental health, including attention and emotional states. Nature and Human Health caught up with her to give you the run-down of what her team has discovered, and how we could all apply the findings to our own lives for greater well-being.

Nature and Human Health Utah: How would you describe the work you’ve been doing around how exposure to natural environments impacts the brain?

Amy McDonnell: Many people report that exposure to nature helps them relax, enhances their ability to focus, and improves their well-being. There is limited understanding of what is happening in the brain and the body to drive these benefits. I aim to uncover the biology behind why nature is so good for us. I measure how the heart and the brain respond to nature—whether that is viewing pictures of nature, being immersed in virtual reality nature, taking a 40-minute walk in nature at Red Butte Garden, or going on a multi-day camping trip in the southern Utah desert. I use a method called electrocardiography (ECG/EKG) to study the heart and electroencephalography (EEG) to study the brain. I believe it is important to elucidate the underlying biological mechanisms of nature’s benefits if time in nature is going to be prescribed from a medical perspective.

NHH-UT: What is the strongest overall finding that your lab has produced about nature and human health?

AM: Our most consistent and robust finding across multiple studies is that brain networks related to attention (our ability to focus) are able to rest when immersed in nature. Natural environments seem to place fewer demands on our attentional systems compared to urban settings, where we are constantly required to multitask, engage with technology, and manage work and life stress. This respite in nature allows these brain networks related to attention to rest and recover, resulting in improved cognitive performance when we return to tasks requiring focus and attention after the exposure to nature.

NHH-UT: What is the most surprising and counter-intuitive thing you’ve found in your research?

AM: I'm curious about whether an individual’s connection to nature affects how much they benefit from spending time in it. For instance, does someone who spends a lot of time outdoors benefit the most out of a short walk in nature, or do they become so used to it that a quick walk doesn’t have much impact anymore? To test this, I administer the Connectedness to Nature Scale with all participants in my studies. Across several randomized controlled trials with hundreds of people, I’ve found that no matter how connected someone feels to nature (i.e., no matter where they rate on this scale), we still see positive changes in the brain, especially related to improved attention. This suggests that whether you love nature or don’t enjoy being outside, you still benefit from it on a neural level.

NHH-UT: There isn’t a lot of continuity or agreement in the field as to how to define “nature.” While it seems easy to understand, it is also elusive. How do you and your team define nature, and what suggestions do you have to streamline the concept?

AM: A single, all-encompassing definition of nature is not possible, as the conceptualization of ‘nature’ differs across time, space, individuals, and cultures. What our grandparents considered to be ‘nature’ is drastically different from what our children will consider it to be in the rapidly urbanizing world we live in. Similarly, Western cultures generally conceptualize ‘nature’ as something that humans are separate from, whereas Eastern cultures generally believe humans to be part of it. However, to empirically test the effects of “exposure to nature” on the individual, researchers must define their own conceptualization of a functional definition of ‘nature’ for the sake of consistency and replicability.

Our laboratory defines natural environments as environments containing vegetation and/or water, with an absence (or inconspicuousness) of man-made structures. This definition applies whether the exposure is a prolonged, in-situ experience (such as in the distant wilderness), a brief in-situ experience (such as a walk in a park), or a simulated representation of nature through images, videos, or virtual reality. It follows then that urban environments are defined by a lack of vegetation or water, and the presence of man-made structures such as roads, buildings, or automobiles.

Although researchers operationalize nature for these purposes, when it comes to individuals seeking out time in nature for personal well-being, I believe they should embrace whatever they personally consider to be nature. What matters most is the experience that resonates with the individual, whether it's a wilderness hike or simply a quiet moment in an urban park.

NHH-UT: What one change to benefit nature and human health could Utah make based on your research, whether economic, infrastructural, or otherwise?

AM: While my research does not focus specifically on children, my work has shown that immersion in nature enhances attention. I strongly believe that integrating nature immersion into our public education system could greatly enhance students' attention and well-being. Research consistently shows that time spent in nature improves attention by reducing mental fatigue and restoring focus. Utah, with its vast and diverse natural landscapes, is uniquely positioned to take advantage of these benefits by making outdoor experiences a more regular part of school curricula.

One approach could be implementing outdoor classrooms, where lessons are held in local parks or school gardens. These settings not only foster hands-on learning but also allow students to absorb the attention-boosting effects of nature. Additionally, dedicated "nature breaks" throughout the school day would encourage students to spend time outdoors between lessons to refresh their minds. Field trips to nearby natural sites, integrated into various subjects like science, history, and art, could deepen students' connection to their environment while enhancing their learning experiences. Partnering with local nature organizations for after-school programs could further support this initiative, giving students of all ages access to nature-based activities.

NHH-UT: If you could advise the general public to apply just one thing for their individual mental health based on your work, what would it be?

AM: Go out in nature- and leave your cell phone behind. My other line of research revolves around human-technology interactions. This research consistently shows that interacting with technology—whether that be your computer, your cell phone, your vehicle, your cellular-connected watch—places continuous demand on the attention networks in your brain. For your mind to truly relax and rejuvenate in nature, you need to give it a real chance to rest, free from the distractions and demands of technology.

NHH-UT: How do you personally put what you’ve learned through your work into use in your own life?

AM: While many of us intuitively understand that spending time in nature is beneficial for our well-being, it’s not always feasible to fully immerse ourselves in natural environments due to the demands of daily life. Like many people, I don’t often have the time to escape to the mountains for a long hike or take time off for a camping trip. However, I’ve learned through my research that even brief encounters with nature—like a walk in a park or arboretum—can still provide significant cognitive and well-being benefits. Even if I only have time for a quick walk or run, I do it in Liberty Park, where I can be surrounded by greenery, rather than sticking to the busier streets of downtown Salt Lake City near my home. I’ve found that these smaller moments in nature, even in urban parks, help me clear my mind and recharge.

When I’m feeling mentally depleted from long hours of computer work, I make it a point to take breaks outside whenever possible. These breaks, even if only for a few minutes, make a noticeable difference in my levels of mental fatigue. Stepping away from the screen and being in nature—whether it’s just taking a walk around the block or sitting on my front porch—helps me reset. The fresh air and change of scenery provide a kind of mental refresh that’s hard to replicate indoors.

A third practice I’ve recently adopted is holding as many in-person meetings as possible at Red Butte Garden. Instead of meeting in the lab or office, I suggest we meet at the garden (which has the added benefit of free parking and free entry with a university ID). This simple change has had a noticeable impact on my well-being throughout the workday and seems to foster more creative and open conversations. I find that the natural setting makes it easier to connect with colleagues in a genuine way. Plus, these meetings often double as light exercise—an added benefit given the cognitive and well-being benefits associated with physical activity.

Thank you, Amy, for all your amazing work and for taking the time to answer our questions this month! And thank NHH readers, we hope this was as fascinating and helpful for you as it was for us.